Ruben Malayan: Saving an intangible Armenian art form, one stroke at a time

August 22, 2019

Since the days of Mesrop Mashtots (the fifth century inventor of the Armenian alphabet*), the Armenian script has played a vital role in the cultural and artistic legacy of her people. Like ancient relics in a museum, each decorative stroke illustrates a story that is steeped in thousands of years of history, literature, art, and religion. Fast forward 1,600 years and this ancient tradition is at a crossroads for survival, with knowledge and usage almost all but forgotten. Yet, once again, one man is at the helm of a movement—a new zartonk (“renaissance”) in Armenian calligraphy. Using a wide range of multimedia, artist Ruben Malayan is ushering in a new era for this unique, yet overlooked art form

From leading workshops in European classrooms to roaming across India in a motorcycle, award-winning art director and visual artist, Ruben Malayan, is anything but idle. His CV reads like a bucket list: travel the world, write a book, work in the Indian film industry, found a project to bring awareness to the Armenian Genocide—to rattle off a few achievements. But perhaps his most impressive—and crucial—role is his artistic creation and activism in the field of Armenian calligraphy.

It is no exaggeration that Malayan is the foremost expert and purveyor of this rich, ancient tradition. He was selected to pen the Armenian chapter of the World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy and is currently working on a book dedicated to the art—the first of its kind—replete with contemporary calligraphic work, which he hopes will serve as a practical guide to learning the fundamentals of Armenian calligraphy.

"Malayan" by Malayan (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

"Malayan" by Malayan (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)In true artists’ fashion, Malayan’s passionate candor is both refreshing and infectious. We spoke with the calligrapher-extraordinaire about his love for this ancient art form, and how we all can play a role in remedying its current predicament.

Educating a new generation on an old art form

Since Armenia gained independence, our letters have suffered massive abuse, a forced Latinization successfully established by bending rules, which were applied to every domain where textual content was presented.

Since Armenia gained independence, our letters have suffered massive abuse, a forced Latinization successfully established by bending rules, which were applied to every domain where textual content was presented.

Lilly Torosyan: It’s no exaggeration that your name has become synonymous with Armenian calligraphy. As a multiplatform artist, how did you get your start in this field, and why are you so drawn to this beautiful—but often neglected—art form?

Ruben Malayan: There are a few reasons for it. I was trained as a graphic artist and, for decades, my occupation was design across various platforms, from print and web to television and film. At the time of my studies, practically no attention was paid to letterforms, except perhaps while doing some mechanical exercises, which do not evoke any emotion, nor produce any result per se. By the way, the same situation persists to this day—higher education in visual arts (I am referring to the local universities and the Art Academy) gives no attention to calligraphy as a means to developing contemporary typography.

Artwork for the popular Armenian rock band, Vishup Ensemble (named after an ancient Armenian dragon creature) in Ruben’s signature calligraphy. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

Artwork for the popular Armenian rock band, Vishup Ensemble (named after an ancient Armenian dragon creature) in Ruben’s signature calligraphy. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)As a visual artist, I have always been drawn to the minimalism of calligraphy and, of course, understood its significance as an art form in the global cultural context. Further, as an art director, I was particularly annoyed by the unprofessional and primitive use of Armenian letters in practically every domain. Typefaces were produced by people who were ignorant of the guidelines and principles of beautiful Armenian letterforms pioneered by the Mekhitarists. I wanted to change that and I fell in love with our letters in the process.

L.T.: As someone who has dedicated so much of his life to reviving Armenian calligraphy, what is it about this art form that sets it apart from others?

R.M.: Calligraphy is an art of beautiful writing and is script in its purest form. Every alphabet is unique and not many nations can pride themselves in having their own letters. Interestingly, our alphabet is still not fully understood and there are many open questions with regard to its development and roots. In that regard, our situation is quite unique.

It’s difficult to point out something specific that I love about it. In general, the most rewarding aspect is discovering new ways of writing expressive and beautiful (though, still legible) characters. The Armenian alphabet is not easy to work with. Many letters closely resemble each other and it is easy to make mistakes. One needs to be very attentive and constantly strive for balanced forms. But unlocking these secrets of beautiful writing is what I love.

We have a serious lack of people who see calligraphy for what it truly is – an art form that strives for perfection and balance.

L.T.: In addition to being an artist, you also teach master courses to students who express curiosity in our beautiful script but may not be equipped with the tools to ask the right questions. What are the most common misconceptions about Armenian calligraphy that you would like to dispel?

.jpg/RubenMalayan-Mashtots-Meditation(2)__324x320.jpg) “Mashtots Meditation”: One of Malayan’s visual interpretations of a religious text. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

“Mashtots Meditation”: One of Malayan’s visual interpretations of a religious text. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)R.M.: There are largely two types of people who practice calligraphy. Some see it as some form of superficial decoration, and accordingly, they usually produce rather mediocre results. If it is seen as just a way to pass time, the outcome is quite predictable. Professionals practice daily and constantly search for new forms. I am often asked to do master classes and workshops and usually find myself in a situation where I need to explain that, in two or three hours, no tangible result can be achieved.

Since a general understanding of visual aesthetics has sunk below adequate levels, students struggle with very basic principles, such as beautiful proportion, balance, and expressivity of line. And it is not just about the technique; it is also about content, since calligraphy that is illegible can only be perceived as an abstract art. In short, doing calligraphy is not as easy and effortless as it may look.

I don't want to wake up one day and see that all that is left is a myth of us once being a great nation, which contributed to the artistic and cultural heritage of the world. I am certain I am not the only one who feels this way. We can only welcome the resources spent on the development of IT technologies, business, etc. But let us not forget that in the big picture, deprived of art and culture, none of it really matters.

“While the prudent stand and ponder, the fool has already crossed the river.” The quote is a line from the 1880 novel, “The Fool,” written by Raffi. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

“While the prudent stand and ponder, the fool has already crossed the river.” The quote is a line from the 1880 novel, “The Fool,” written by Raffi. (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)L.T.: You have stated, the “art of beautiful writing is the link to our past and with the attention it deserves, it can help to shape our future as a nation of rich artistic heritage.” Why do you believe that more isn’t being done to preserve and progress this ancient art form, and how can we change that?

R.M.: To me, the situation is paradoxical. On the one hand, we constantly speak of our alphabet, of its importance to us as a nation, while on the other hand, we do next to nothing to study it or present it adequately to the outside world. There is no institutional approach, no academic research, or at least, none that I am aware of. During the Soviet period, there were books published on the subject, and some progress was made in this field of study.

Prior to that, the only institution that gave our alphabet the attention it deserves was the Mekhitarist Order. Yet their legacy is left to gather dust on our bookshelves. This crisis threatens the very foundations of our culture; the diaspora faces a serious threat of linguistic and cultural assimilation and, unless we review our attitude, we may gradually find ourselves unable to sustain our cultural identity.

As for higher education, the situation is critical; the education system in Armenia (and not just in the Arts) is in a deep crisis and needs to be seriously re-evaluated. We need to go beyond empty words and make teaching a priority, and the proud profession it once was.

Calligraphy needs to find its way back into the school system. It needs to be taught from a very early age, perhaps as soon as children learn their first letters. It would teach the children discipline, develop their imaginations, and above all – cultivate their love for their culture.

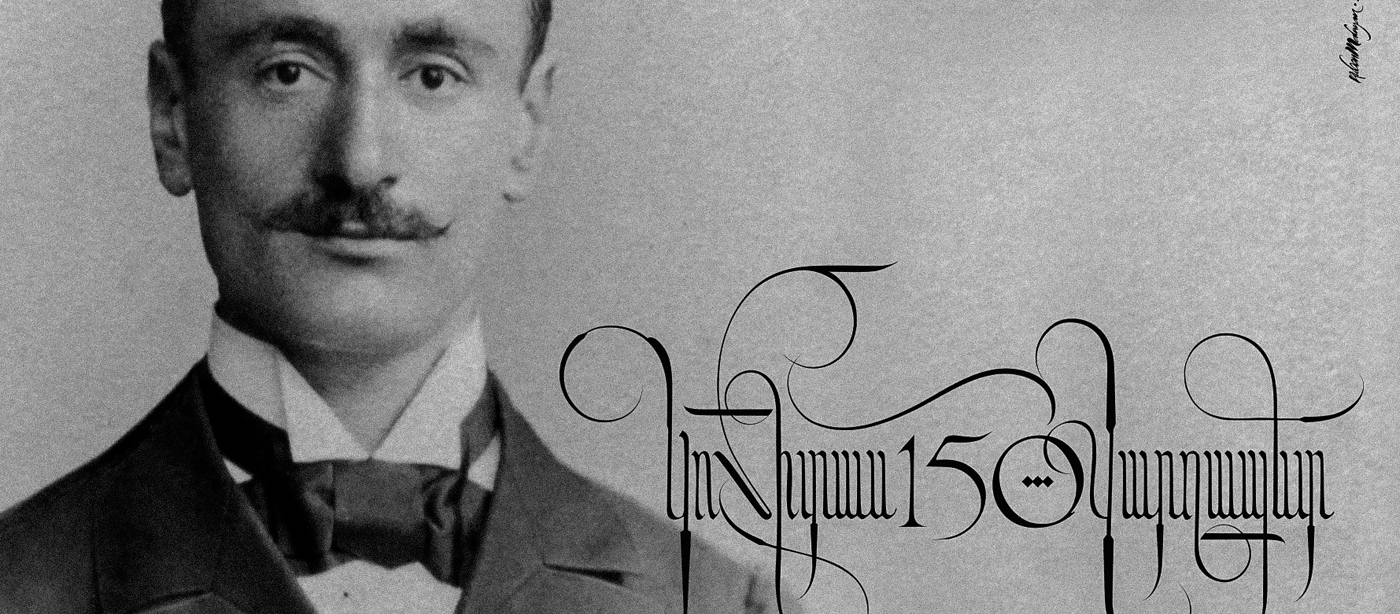

Malayan's graphic commemorating Komitas Vardapet's 150th anniversary (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

Malayan's graphic commemorating Komitas Vardapet's 150th anniversary (Graphic courtesy of Ruben Malayan)

L.T.: How can we learn more about Armenian calligraphy?

R.M.: First of all, fall in love. That’s the key. Try to learn by looking at beautiful examples, study letterforms attentively, and always aim as high as possible. Remember that the Armenian language and, by extension, the writing is what makes us who we are. Put your culture above everything else, be ready to do some hard work, and never betray your ideals.

Check out Ruben Malayan's website to learn more about his work. While you're here, also visit our photo album below to see more of Malayan's calligraphy art!

* Though Mashtots is widely regarded as the creator of the Armenian alphabet in the early 5th century AD, many scholars are not convinced. Some argue that the foundations of the alphabet were already in place and Mashtots merely “rediscovered” and systemized it. This is a heated debate amongst academics. For more information, check out The Heritage of Armenian Literature by Agop Hacikyan.

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!